As I mentioned in an earlier post, there’s an exhibition of works by Vasyl Yermylov (Vasily Yermilov, Василий Ермилов, 1894-1968) at the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow. Yermylov was one of the preeminent Constructivist artists of the Ukraine, and the leader of the Kharkov avant-garde circle. Western critics have named him one of the finest designers of his generation. His works – art, graphics, sculpture, design and book illustrations – are to be found at the exhibition.

Yermylov’s art is a synthesis of different artistic streams, amongst which are expressionism, cubism, futurism and neo-primitivism.

His art is laconic and he can easily be called one of the forerunners of minimalism and conceptualism. In his arsenal are two or three localised colours, two or three geometric elements, two or three material textures (tin, wood, and tar). He sought skilful techniques of polishing, grinding, powdering, contrasting oval and angular planes, perfect proportional order; in his works are high compositional and rhythmic effects.

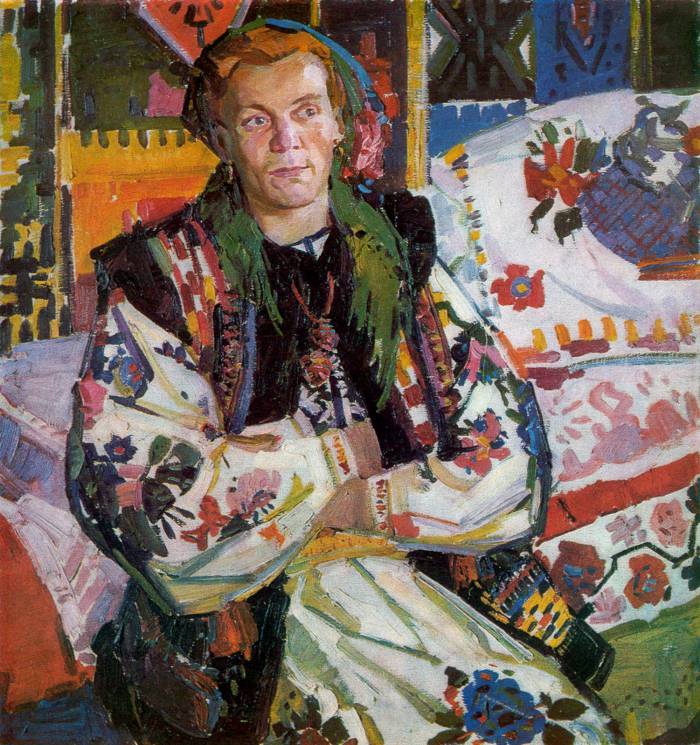

In Yermylov’s works is evident a deep love for aspects of Ukrainian folk art and handicraft, which he elevated to the rank of high art, with deep care and harmonic brightness in his treatment of surfaces.

The exhibition comprises several thematic divisions:

Sculpture

The major sculptural works (such as Agitprop platform for the installation for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution, 1927) are preserved only in the form of sketches and old photographs. The sketch for the sculpture “Three Russian revolutions” itself resembles a complete work of art. A special place is occupied by the memorial project “Monument of Lenin’s era” (1960s), a working model of which is represented in the exhibition.

Painting

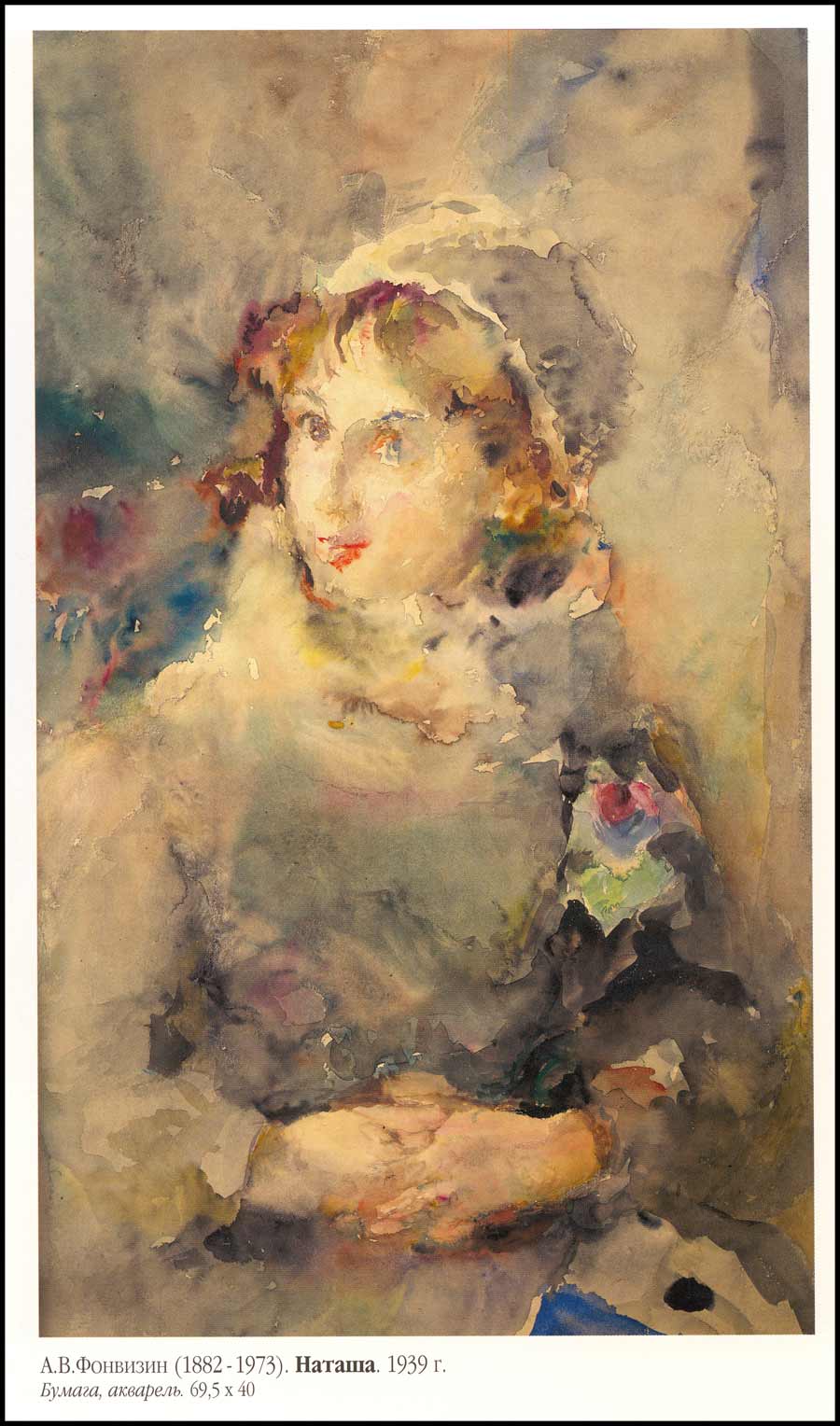

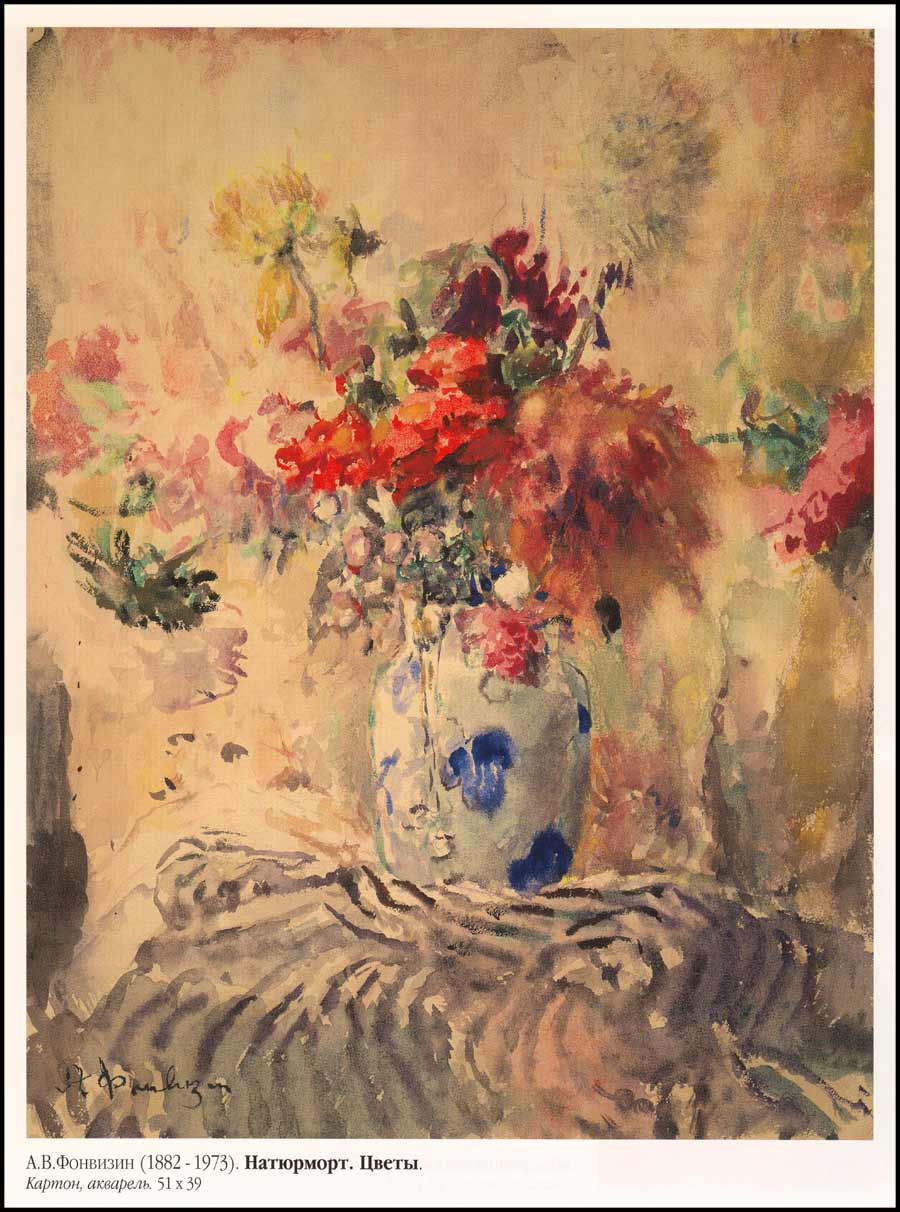

Among the exhibits are a few variations of “Guitar” (1919), “Mandolin,” many graphic male and female portraits, and examples of sculptural art: relief and bulk composition. From 1922 Vasily Yermylov created a series of bright contra-reliefs and “objets d’art” of various types of wood and sheet metal, such as the schematic, “A Portrait of the Artist A. Pochtenny.” Among the experiments in the field of photomontage is notable for the relief of “On the Beach (morning, evening)” (1935), combining painting, photography and relief.

Poster Art

No less interesting is the work of the artist in the field of advertising and poster art, which became a symbol of the Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde. Yermylov’s contributions are propaganda posters, sketches of packages of cigarettes, a bottle of cologne “Victoria” and the creation of a logo Kharkov perfumes and cosmetics factory (1944).

Architecture and Design

Design sketches for the Kharkov House of Pioneers (1934-1935) – self-contained abstract paintings, colorful and decorative, and in spite of a modest scale, monumental. In the interior design, he successfully used a combination of different colours and the plasticity of simple geometric volumes.

Book Illustrations

Appearance of numerous books and magazines based on the use of different printing elements, bands, circles, photomontage. He created a new “Yermylovsky” monumental font, which was a breakthrough in printing design. A striking example is the typesetting of books of poetry of Velimir Khlebnikov, a friend of his, where he created a unified style for Khlebnikov’s many books, including “Ladomir” (1920).

Vasily Yermylov’s oeuvre despite its striking originality, remains open to dialogue with the works of other masters. His open, creative aspirations, attitudes, philosophies existed in the context of national and pan-European artistic processes of the first third of the twentieth century, which created a singular space of the avant-garde art.

Lady with fan. (1919). (Photo: Multimedia Art Museum).

Portrait of the Artist A. Pochtenny. (1924). (Photo: Multimedia Art Museum).

Journal Cover for ‘Avant-Garde’. (1929).

Beautiful Ukraine. (1920).

Plans for the future.

Day of Art. (1920s).

Argentinian tango. (1920s).

Sketch for interior design of the Kharkov Palace of Pioneers. (1934).

Interior design for Kharkov Palace of Pioneers. (1934). (Photo: Multimedia Art Museum).

Advertising poster for cigarettes. (1925).

Decorative composition. (1960s).

Study for the panel ‘Music’. (1964).

Sketch for mosaic panel ‘Flowers’. (1960s).

Budenovtsy. (1962).

[Translated from Modnitsa’s article ‘Exhibition: Vasily Yermylov. 1894-1968‘, at Fashionista.ru.]