That is how the Great Soviet Encyclopedia introduced this artist of world significance. Certainly, the artistic career of Yavlensky is associated with Germany. But he received German citizenship only at the age of 70. And he’s buried in Wiesbaden in the Russian Orthodox cemetery. Therefore his oeuvre may be rightly said to illustrate the history of art both in Russia and in Germany.

In Russia

Alexei Georgevich Yavlensky (Alexej von Jawlensky) was born in 1864 in Torzhok (Tver oblast) in a family connected to the Rastopchin counts. The boy was expected to take up a military career: upon finishing cadet school he studied at the Moscow military academy and graduated as a lieutenant in the Grenadiers. But since his teens Alexei had been interested in art; receiving a special dispensation (which was necessary for officers) he joined the St Petersburg Academy of Art where he attended classes taught by Ilya Repin.

In the academy, Yavlensky became acquainted with Marianna Veryovkina (1860-1938), a daughter of an army commander. She was four years older than Alexei and had already established herself as an artist, but recognising Yavlensky’s extraordinary gifts, abandoned the art to become his ‘common-law’ wife, and devoted herself entirely to the development of her husband’s talents.

A Wonderful and Joyous Time of Work

In 1896, Alexei and Marianna (who had become financially independent owing to a rich bequest from her father’s estate) moved to Munich, the German Athens. With them went 11-year old Yelena Neznakomova, Marianna’s ward.

Yavlensky joined the famous atelier of Anton Aschbe. At the time, there were many Russians who would attain later fame: Grabar, Dobuzhinsky, Bilibin, Kardovsky, Kandinsky, … Kandinsky got acquainted with Yavlensky there, which was the beginning of a long friendship and collaboration.

Schokko with Wide-Brimmed Hat. (1910).

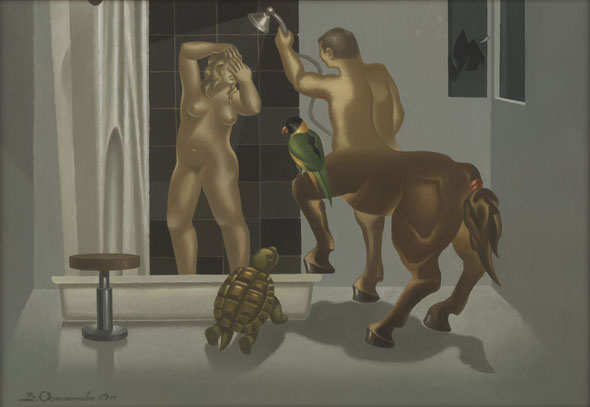

Veryovkina and Yavlensky travelled extensively, immersing themselves in European culture. The young artist was enraptured by all forms of modern art – impressionism, constructivism, cubism. Acquaintance with Henri Matisse and his work inspired Yavlensky’s creation of colour paintings, for which he earned the nickname ‘Russian fauvist’. This passion changed expressionism, into which the artist brought his individuality. His main interest was the ‘life of colour’. One of the most characteristic works of the period is Schokko with Wide-Brimmed Hat.

In 2008, this painting was sold for £8.4 million at Sotheby’s.

Off and on, Yavlensky would return to Russia to exhibit his works. But his artistic and organisational activities remained associated with Munich. In 1909, with Kandinsky he created the “New Art Association. Munich.” which included artists from different movements, who were, however, united in their typical rebellious spirit and protest against traditional art. Next, Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) appeared, established together with Kandinsky and the German painter Franz Marc.

Girl with red ribbon. (1911).

Girl, folding hands. (1909).

In 1910, Kandinsky came up with his first abstract creations. Although Yavlensky’s remained close to his friend’s artistic investigations, he never completely took up abstractionism in the full sense of the term. Munich was a happy period in his life: he painted and exhibited copiously, his works sold successfully. The Yavlensky-Veryovkina house was frequented by friends and visitors. In Murnau, where Kandinsky and Yavlensky were neighbours, their association was particularly close. The artist Gabrielle Münter, Kandinsky’s intimate, wrote in her diary: ‘a wonderful, joyous time of work with constant discussion of art with the inspirational Gisellists.’ (Gisellists was a term originating from the name of the street that Yavlensky lived on in Munich).

Other Moods – Other Art

With the beginning of the first world war, everything changed. Kandinsky returned to Russia. Franz Marc joined the army and soon after died. In August 1914, Yavlensky moved to Switzerland with his family, to St Prex – near Lausanne – on the shores of Lake Geneva. The sharp change in fate oppressed the artist – his works became filled with symbols and simplified forms. This is reflected in his famous ‘Variations on the theme of Landscapes’ of the period.

Everything changed again when he became acquainted with the 25-year-old Belgian artist Emmy Scheyer (1889-1945). Having encountered his canvases at an exhibition, she had been so taken up with them that she sought out the artist, saw his other works, and as a result decided to abandon her art and to devote herself entire to Yavlensky and to promote his work. Such was the amazing impact of this man and his works on women! This friendship (or was it love?) determined the artist’s fate. He was unwilling and unable to sell his paintings or to engage in discussions with exhibitors. Emmy took all this upon herself in the capacity of his private secretary.

Self-portrait. (1912).

In 1917, the artist began the series Mystical Heads. In the beginning, these were stylised portraits of Scheyer, which then gradually transformed into ‘heads’ – abstract images without similarity to any prototype.

Life in the small town burdened Yavlensky, and the family moved to Zurich. But his health suffered, and on the advice of doctors, they moved to the south of Switzerland, to Ascona on the shores of Lake Maggiore. The years spent here were considered by Yavlensky as ‘the most interesting in his life’. He worked intensively, creating one series after another. These were ‘Abstract (or constructive) heads’, then ‘Holy faces’. The faces were ascetic, stern, filled with spirituality – limned only with colour lines and ink patterns. ‘I realised that the artist must express himself through colour and form, … whatever is in him is from God.’

Wiesbaden

By 1921, there had been many changes in Yavlensky’s private life. His platonic relationship with Marianna turned into an affair with Marianna’s ward Yelena, who, at the age of 17, gave birth to his son, Andrei. Officially, he was considered Yavlensky’s nephew. Yavlensky, however, wanted to marry Yelena and legitimise his son. Marianna was against this, and so after thirty years of life together, she and Yavlensky separated. She remained in Ascona, where she lived another seventeen years till her death. She was buried there. In the town museum, several of her works are exhibited. Yavlensky moved to Wiesbaden with Yelena, now his wife, where they lived for twenty years until his own demise.

The First Green in Spring. (1915).

In 1924, Yavlensky and Kandinsky created the ‘Blue Four‘ (Die Blaue Vier), an association including Paul Klee and L. Feininger. Scheyer now organised exhibitions and sales of the works of the group in Germany and the USA.

In 1927, fate sent another guardian angel. This time it was Lisa Kümmel (1897-1944), a painter, a master of applied arts and a designer. One of his friends from later life wrote about this friendship (or was it again love?): ‘This woman was with him every day. She took care of his correspondence, created a catalogue of his oeuvre, wrote his memoirs… Kümmel selflessly sacrificed herself for the sake of the man and his work.’ Yelena didn’t understand her husband’s quests. ‘All the time he draws these idiotic crosses,’ she said.

At this time, he became friends with another admirer of his talent. The name of this artist and sculptor was Hanna Bekker vom Rath. She set up the Association of Friends of the Art of Alexei Yavlensky, the purpose of which was to provide material aid to the artist. Members of the association paid monthly dues which allowed them at the end of the year to obtain one of his paintings. A large part of the collections went to the support of Yavlensky’s family. (In the preparation of this essay, we visited Wiesbaden museum again. Not a few works of the artist are on permanent loan from the collection of vom Rath.)

His last years were the most important for the artist’s career. In his personal life, there were terrible events. The nazi regime confiscated his works, relegating them as ‘degenerate art’, and prohibited him from participating in exhibitions. Ironically, Yavlensky received German citizenship in 1934, having waited four years for it.

Meditations. (1934).

Illnesses progressed. His eyesight worsened. He suffered from acute arthritis. The artist could not use his right hand, so he guided the brush with his left. Nevertheless, despite no expectations of exhibiting his works, he continued to paint. It is said he worked in ecstasy, with tears in his eyes. ‘My work – this is my prayer, my passionate prayer, expressed through paint.’ Friends called him Ivan Karamazov, and experts consider him one of the prominent representatives of modern religious art. His last series, created in 1934-1935, was called ‘Meditations‘ and conveys the tragic state of his soul. The image has become stark in contrast, grim. This is a combination of planes crossed with vertical and horizontal strokes. Out of the black background emerges a stylised face, a cross. Critics consider ‘Meditations’ the acme of Yavlensky’s oeuvre, unparalleled in the art of the 20th century.

Memory

Yavlensky died on March 15, 1941 at the age of 76. He is buried in the Russian orthodox cemetery of Wiesbaden. The gravestone is a white marble cross on which appear the words ‘Thy will be done’. Below appear the names and dates of Alexei and Yelena Yavlensky.

Yavlensky’s archive is in the Swiss town of Locarno. His granddaughters Lucia and Angelika arranged and published a four volume catalogue of the great painter’s artistic inheritance in 1990.

Yavlensky’s paintings adumbrate museums in Europe and the US; numerous researches have been performed on his work. At long last even his countrymen saw his works: an exhibition at the Russian Museum was held in 2000.

One of the greatest collections of his works is at the Wiesbaden museum. Besides the permanent collection, there are also special exhibitions devoted to the artist. In October 2011, an exhibition titled ‘Light – abstraction – series’ opened at the museum.

In Wiesbaden too an art prize in Yavlensky’s name has been set up; a local high school is named after him; there is a street – Jawlenskystraße; and a memorial tablet appears on the wall of the house he lived in (Beethovenstrasse 9).

[Loosely translated from the Neue Zeiten article by Ilya Dubinsky, October 2011.]