So here we are among the works by artists originally displayed as part of the Jack (or Knave) of Diamonds exhibition in Moscow. The notes for each painting are taken from the exhibition cards of the Courtauld Gallery, London.

Mikhail Larionov’s (1881-1964) work below was displayed along with Still life in a Major Key at the Golden Fleece exhibition in Moscow in 1910. The Russian avant-garde artists had an abiding interest in the union of music and painting.

This painting was in the first Jack of Diamonds exhibition in Moscow from December 1910 – January 1911. “The nude female bathers form a scene similar to the works of the German Expressionist group the Bruecke (Bridge). Larionov’s use of red-orange and green, opposite colours on the colour wheel, define the figures with a jarring, clashing force.”

Aristarkh Lentulov (1882-1943) returned to Moscow and painted this based on his impressions gained from his Parisian life among the French avant-garde. “The artist uses a radical style to depict a very traditional subject, giving the roses a monumental quality through his layering of petals and bright blocks of colour.”

Natalia Goncharova’s (1881-1962) series of harvest paintings appeared between 1908 and 1911. She imagines a scene of cypresses and pink mountains, and the women’s outfits are unlike those she usually depicted Russian paintings in. Apelsinia was a name she invented for her solo exhibition in 1913 in Moscow. “The work reveals her taste for the exotic and interest in the art of Paul Gauguin.”

Vladimir Burliuk (1886-1917) was influenced by Cezanne and Cubism. “He often fractured his paintings into interlocking irregular segments, as if translating the principles of stained glass onto canvas.”

Olga Rozanova’s (1886-1918) typical style of simple and energetic brushwork and bright colours is exemplified in this work, executed three years before her death. The playing cards theme was one she returned to throughout her life, “emphasising that her art was based on card games often played in streets, bars and funfairs.”

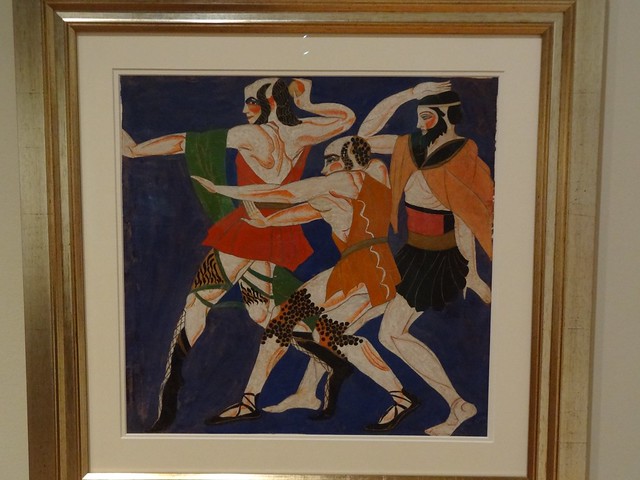

Innokenti Annenesky’s play Thamyris, The Cither Player (Famira Kifared) was staged at the Moscow Chamber Theatre to Alexandra Exter’s design, which incorporated traditional art of her native Ukraine and referenced ancient Greek friezes. “With their graphic clarity and arrangement of bold colours, Exter’s designs contributed to a rhythmic framework shaping the performance itself.”

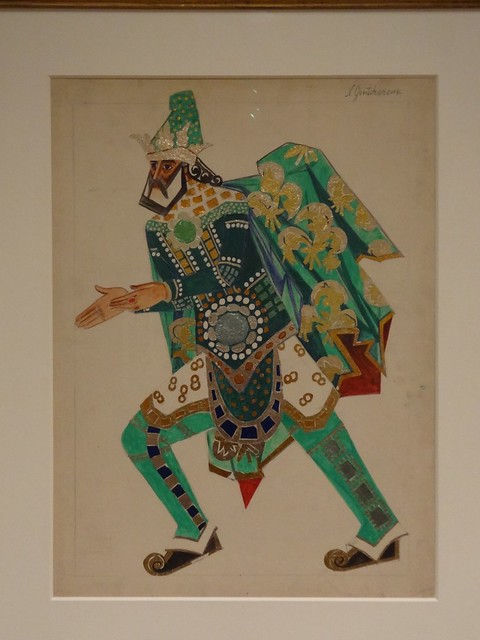

This was a design created by Goncharova for the astronomer Magus in a ballet (Liturgie) that never saw the light of day. Here she displays her interest in Russian folk art, peasant embroidery and icon painting. She was at the same time beginning her fruitful collaboration with Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.