Q: With which museums did you have the most effective relationships while working on the Encyclopedia?

A: We worked with an enormous number of museums, but mainly with the Russian Museum, the Tretyakov, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki, where the Costaki collection is; we received lots of slides. But in fact we collaborated with many regional museums, after all the avant-garde in 1919-20 had spread across all of Russia. There was an ideological programme to establish contemporary art museums. I’ve been working on the subject for many years and can say that nearly a thousand works were transported out of Moscow to provincial towns, wherever there were some sort of art schools. Kandinsky, Malevich and lesser artists were taken to around 40 towns. In later years, about 30% were lost, while the remainder were preserved in museums, and we obtained reproductions from them.

Q: In the beginning of the interview, you said you were thinking of publishing one volume. Now there will be three. I’ve held the first two in my hands, and they are pretty heavy, and more importantly expensive. Truly the Encyclopedia is a seminal work of exceptional importance, but who can buy it for 22 thousand rubles? Libraries?

A: Of course we’d like libraries to have these books. There is an idea to find money to make additional copies – for libraries and museums. With the majority of museums we have had agreements and we’ll give them copies. For them, our book is very important. Several collectors have also written to me, saying that the Encyclopedia has helped them understand some things, and find attributions for works in their collections.

Q: How is it so expensive? Because of the illustrations?

A: No, not just that. We paid honorariums to the authors and museums for the rights. The cost of all the work is not small.

Q: Can we expect that in the Non/fiction exhibition the books will be a bit cheaper?

A: Certainly. There will be the lowest price at which the books can be bought, and there will also be a student discount for those with student IDs. After all, we are humanitarians.

Q: The budget always affects the final result, whether it’s big or small. Did your funding change during your work?

A: The budget kept climbing all the time, and I’m very grateful to our sponsors who took care of all the costs and never argued with me. The number of authors kept rising; we also had a powerful editorial team: a literary editor, a producer, a proofreader. All of them read it. Though I still to this day find various errors in the final book. But as an old-time worker in the industry, I understand that these are unavoidable. In one place, the photographs of two women artists are mixed up. I hope that after the third volume comes out, we can make an online version of the Encyclopedia and a website dedicated to it.

Q: An electronic version can be expanded, broadened, and importantly – constantly updated. That is, in the future, do you plan to continue working on the text?

A: Of course, there is work for the future, but I don’t know for how far in the future. The site could go beyond the Encyclopedia, there could be articles on major artists, including Malevich and Kandinsky.

But first, the third volume needs to come out, which in fact is the most difficult. If in the first two books everything is clear – the alphabet and the last name determine the location of the artist, then in the last tome it’s not even clear what title to give to some articles. For example, everybody knows the (ГСХМ) State Independent Artists’ Studios, which were established under the Stroganov school and the Moscow school of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. These were transformed into a completely different status, new teachers appeared there who taught the avant-garde. These studios then expanded to a dozen and a half other towns – Tver, Novgorod, Vitebsk, and they were all called differently: ГСХМ, СГХМ, ГОСХУМ. In Soviet times, they loved abbreviations, but there was no uniformity among them. And how to bring them all into a single view, I still haven’t decided. The third volume will also contain articles on exhibitions, journals, publishers, or even about some artistic cafe. We’ll design it differently, with pictures not appearing stand-alone, but rather within the text. This will make the design more difficult, but there’s no alternative.

Q: Do you think that in the first two volumes you have been able to achieve a stylistic coherence, an encyclopedic uniformity?

A: We tried to do so, though there isn’t such a rigidity here as in other encyclopedias where everything is specified: write this way and no other. As our theme is art, not physics, not an exact science, we decided to allow our authors some freedom in language. One of our principles was to allow an authorial point of view. We welcomed this, and when it was missing, we had to add it ourselves. Rakitin and I wrote 150 articles each, and edited many others.

Q: What would you consider your greatest achievement in the Encyclopedia?

A: I think we have revived names that had been forgotten by everyone. This is the main thing. About famous artists, it’s always possible to find something, but about those who established the backdrop, there’s almost nothing. Malevich, for instance, had eighty students in Vitebsk, and we wrote articles about all for whom we were able to find some information. We found, maybe, twenty people. Of course, among his students were Chashnik and Suetin, but there were also complete unknowns – for example, the Finnish artist Ahola-Valio.

Undoubtedly, with the release of the Encyclopedia we also have plans to promote and popularise the Russian avant-garde, because it is not well-known in our country. Many artistic types like to brag, “I don’t like the avant-garde! Anyone can paint like that, anybody can paint the Black Square.” You understand that this is the favourite excuse of everyone who understands nothing about art. Well, be the first to paint it, then! Invent it! There is much for the Russian to be proud of; they only need to know more about the time.

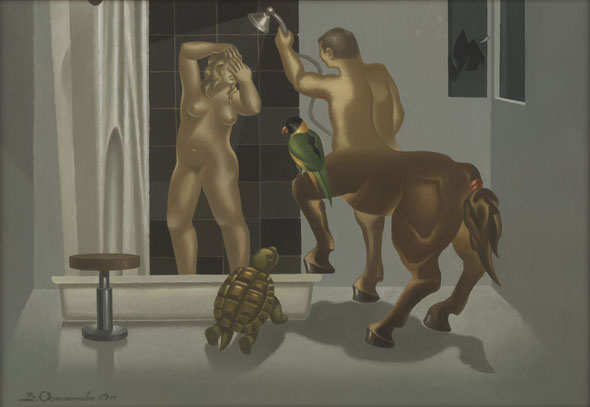

Black suprematist square, by Kazimir Malevich. (1915).

Q: The avant-garde is such a diverse phenomenon, it has many different faces. You have combined them into one publication, and more importantly – showed the real faces of an enormous number of avant-garde artists. Did some general image develop?

A: When you leaf through the book, you see hundreds of people who perished tragically, because it was a terrible time, the Civil war, the terror… There was an incredibly talented artist, Semashkevich, who was executed in 1937, his paintings confiscated and lost somewhere in the Lubyanka. We found around ten works of art, and yet he had been extraordinarily prolific.

Many people died tragically, many abandoned the avant-garde because life forced them to: they couldn’t feed their families, they couldn’t survive solely on their art, they had to change job. But still they wouldn’t be part of the crowd, they were engaged in art because they loved it. It’s a slice of an entire era: everything that happened in the country in those years has been reflected in the art. And that’s why the multifaceted avant-garde is so striking. I think we were able to demonstrate it – and that’s also and important achievement of our Encyclopedia.

[Translated loosely from Tatyana Yershova, «Мы вытащили имена, о которых все забыли»: Как искусство русского авангарда собрали в энциклопедию. Lenta.ru, Nov 28, 2013.]