In the genre of the still life, there are only a few examples from Zinaida Serebriakova’s oeuvre. In her catalogues, we find around twenty works of still life. Notwithstanding the fact that the still life is one of the first exercises in an artist’s education, in Zinaida’s case it appears at a fairly advanced age. Her first piece, called ‘Flowers at the window’, dates from the 1910s. It’s possible that she rarely executed still lifes, or possibly they sold rapidly and have not been seen since. One can take as long as one needs with a still life; there is no sense of urgency that might result from the changing character of a portrait sitter. Zinaida involved herself in still lifes only when (in her own words) a model for portraiture was unavailable. She was attached to the classical arts, and the classical artists rarely painted the ‘nature morte’. In the academy, the still life belonged only to trainees. Briullov hardly ever painted any; neither did Fedotov. Repin painted ‘Bouquet‘ in 1878 in Abramtsevo, and ‘Apples and Leaves‘ the following year, which (given its pretentions towards portraiture) he never exhibited, and assigned as an exercise to his student Serov, in whose hands it appeared fresher and filled with colour.

The genre of the still life was not popular in the 19th century, but obtained some measure of respect and recognition in the 20th, during which it underwent an extraordinary expansion in its breadth. Now, the viewer experienced not only the specifics of a particular lifestyle, but also those unique features that are inherent in certain individuals. The underlying essence of the world phenomenon was revealed more fully. The concept of beauty in the still life became more diverse, the artist seeing the wealth of forms and colors where previously no one had found anything remarkable. Sometimes it does take a still-life to allow us to express difficult and sometimes conflicting ideas about the world.

There are some objects that an artist will only rarely take up, for fear of appearing amateurish. In Zinaida Serebriakova’s still life ‘Apples on branches‘, we observe a beautiful picture: yellow apples and rich green leaves. The branches and the gleaming leaves and apples are equally numerous. The lovely mosaic is not merely decorative, but is deeply realistic: the apples are painted vividly, almost sculptured. A fine line, nearly hair-thin, distinguishes the image on the canvas from a real tree. The work is accentuated by an attention to detail: we can almost sense the taste and smell of these fruit. Here is celebrated a festive apple pie or a preserve; still these fresh apples are somehow better: they’ve been warmed in the sun, they crunch satisfyingly between our teeth. Here too is the pride in her work – ‘we grew these apples!’ It is a hymn to nature.

Zinaida returns to the same motif in 1930, in the work titled ‘Pears on branches.’ Again the flavour and aroma and the feeling of weight is evoked through the associations and emotions of the viewers, who relate to the objects through their own experiences of life.

The skill of the artist lies in the fact that the representation of the beauty of nature pushes the imagination and emotion of the audience, enriching it with new discoveries.

Serebriakova’s ‘Still life with the Attributes of Art‘ is a traditional composition for her. As is usual in works with the same theme, there is an ancient mask, a box of paints, a scroll, while in the background are glass bottles with powdered pigments and bright ceramic mortar. Similar technical themes often appear in the oeuvre of artists. In 1913, P. P. Konchalovsky painted ‘Dry paints‘ in which his interest in bright pigments – orange with cobalt, crimson and ochre – was clearly evident. The canvas was made up in a rough and rustic manner. Serebriakova’s painting is softer, more tactful. In the books, in the paint-spattered brushes, in the sheets of drawing paper left on the table, reside the warm touches of the artist, reflecting her love, keen interest and attachment to the ever-present tools of her trade. And it may be precisely in this humanity of the objective world that we find the fullest interpretation and attention Zinaida gave to reality. She communes with the tools that serve her like faithful old retainers, recognizing so well their valued quality. The world that Serebryakova opens before us is complete, smooth, clear, warm, filled with light and harmony.

The next still life is a more modest work titled “Herring with lemon.” There is a certain irony noticeable here: the lemon is partially peeled with a strand twisting gently: it has a pretension to gentility, while the herring beside it is such a simple, common fish. But in this canvas is the poetry and beauty of the quotidian human existence.

The painter observes the capricious play of folds, reflections and shadows, from which emerge everyday objects, surprisingly convincing in their reality. Transferring the uniqueness of each object, the artist perceives their generality and intrinsic worth.

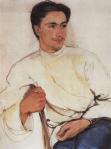

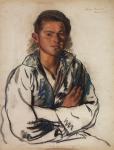

Another painting by Zinaida Serebriakova is the still life with portraiture. Titled ‘Katya with still life (1923)’ in the catalogue, the artist merely marked it as ‘Still life‘. In other words, Zinaida herself considered this piece a still life, rather than what we might judge a portrait of a child. ‘Baker in the Rue Lepik‘ and ‘Vegetable vendor, Nice‘ would be two other examples in this blended style. In Zinaida’s art, still life fulfills a complementary role to the primacy of portraiture.

“She successfully portrays a man in his life, in his home environment, surrounded by the familiarity of everyday items,” wrote A. Savinov. “A master of still life, she happily painted in her portraits’ backgrounds books, washing jugs, paintings hanging on walls, paint cans, a mirror with her reflection. A person is shown at home or in the company of those things that he holds dearest and most intimate to himself.”

At an exhibition in Brussels in 1928, she displayed a still life with fish. Four other still lifes feature in an exhibition catalogue from St Petersburg the following year. In 1931, she painted ‘Basket with fruit by the window. Menton.’ In 1932, she returned to the genre with ‘Still life with asparagus and strawberries.’ In 1934, Serebriakova wrote: “I want to attempt flowers – tomorrow I’ll go to the big market, which is open only till 9am; hopefully, they are cheaper there… It is strange, never in my life did flowers ever work out for me. After all, this is a subject that sells better than others.”

The Art Nouveau paid attention to flowers. There are sketches of flowers by (Mikhail) Vrubel. Flowers in the hands of heroes appear symbolic. In graphic books, flowers become vignettes. In the Art Nouveau, flowers signified meanings derived from myths. Tulips, orchids, lilies, pitchers signified tragedy, wounds and death. Bluebells signified desire. Sunflowers denoted an ardent thirst for life. The rose and the narcissus were also favourite flowers for the Art Nouveau. But even other flowers attracted Serebriakova. In the 1995 catalogue ‘Z. Serebriakova’ there is a print of her ‘Basket with flowers‘. Here you don’t find fiery roses or gladioli or lilies; instead there are daisies and carnations. One must possess a great creativity and experience and a keen eye to achieve the simplicity in which the image, while maintaining ease and naturalness, creates a sense of the inner pulse of life. During the same period, she painted ‘Basket with grapes’. Turning our attention from object to object, we divine in them a hidden spirituality. They sparkle in the radiance of sunlight, like a mysterious glance a-quiver with emotion.

And yet such a – shall we say ‘feminine’? – motif rarely appears in Serebriakova’s oeuvre. B. M. Bialik wrote, “Her still lifes – these are the lives of kitchen utensils, vegetables, the simple articles of daily life, flowers and the fruits, which talk not so much about the uproar of nature as about its generous variety. Her still lifes do not boast of wealth, and do not demonstrate innovations in painting; they are restrained and universal. But in this routine is the truth and sincerity of life. Sometimes her paintings, where baskets reign with flowers, appear like fragments from a film, but they are always an ode to the gifts of the earth.”

Wriggly carps appear in ‘Fish on greens‘ (1935). They lie on laurel branches, while in the background are cauliflowers, tufts of white radish, scarlet carrots. The vegetables are masterfully painted. The scale of the composition in the still life is focused on the size of a minor room, hence its great intimacy compared with other genres. Glancing into the surrounding space, penetrating its laws, unraveling its secrets, the artist reflects it in her work. Depicting her own relation to reality, she emerges not only as an observer, but also as an interpreter of nature.

Still life, more so than any other genre, escapes from verbal descriptions: it is necessary to scrutinize it, to be immersed in it. In this sense, still life is a key to any painting, as it teaches how to admire the image, its beauty, power and depth.

In 1936, Serebriakova painted ‘Still life with vegetables.’ That same year she again returned to the theme of grapes (‘Grapes‘).

“The vine ripens,” she wrote. “All the residents have brought out their barrels and baskets, and shortly they’ll begin gathering it and making wine. Everyone here drinks their own wine, and in our house too, we’ll be making it. As soon as it starts to rain, I get back home, and start to paint nature mortes with grapes, my eternal theme.”

White and black grapes are painted with care and zeal, and little playful whiskers emerge from the bunches.

Serebriakova did not paint crystal goblets and slaughtered game on marble tables – her still lifes are far simpler. The canvas ‘Vegetables‘ (1937, Benois Family Museum) can also be called simple, but how bright are its colours: emerald greens, pink potatoes, violet plums, orange apricots. On the juice-filled shadows fall bright spots of light. The material completeness of the image, and the timorous animation of the life of objects suggest a sensation of romantic elevation and emotional stress. The painting was never sold; it was gifted to the museum where it has been preserved in the archives, open to admiration only of the staff.

V. P. Knyazeva wrote, “Working on still lifes, the artist studied different spaces, textures, colors and contrasts with tireless attention. In the works of her last creative period one finds the same love of the material world as those of her works in the early 1920’s. At the same time, a complexity of relations between color and light appeared in them, more fully conveying the richness of the earth and reality.”

In the genre of still life, one can count Serebriakova among the followers of (Jean-Baptiste-Siméon) Chardin, who said that “one should paint not with pigments but with feeling”. What Alexander Benois said of Chardin was equally valid of Serebriakova: “Despite his apparent simplicity, Chardin is a great artist, a great magician of art who is aware of such beauty around us as has eluded everyone else… In order for a simple circle or a bunch of grapes to appear not only a beautiful piece of art, but also a real poem filled with seduction, requires a special revelation, a special gift to see beauty in everything.”

The still life is distinguished by special principles of composition: the objects are usually drawn close by, so that their appearance implies their own physical characteristics, their weight, shape, form and texture, serving to clarify their interaction with their environment. In the earthly beauty of the objective world, in the identification of its material nature, in the lushly scenic modeling of volume and content of the object, in the love of the wealth and fruit of the earth lie the foundations of the genre.

Often one speaks as much of the associations as of the special quality of the still life. As much as the objects of a still life reveal their internal reality, so do they speak of the qualities of their owner; in this, the still life reflects the world view of its author. But it is hardly obligatory to seek out hidden stories in a still life.

In 1940, Serebriakova painted ‘Wild flowers‘; in 1948, ‘Still life with apples and round bread‘; in 1950, ‘White lilies in a basket‘; and in 1952, ‘Still life with a pitcher‘. With gradually changing understanding of artistic possibilities, the subject of painting lost its traditional intimate nature. The artist sought to convey in a still life a complex poetic content which is difficult to express in words and can only be comprehended by an imaginative perception of the world. Yes, the world is harsh, as it were, she says, but this severity has its own beauty. With all its tensions, an ascetic way of painting a picture clearly reveals the features of a harmonic coherence. The shape, size, texture, materiality of the objective world, just like the defining features of our favorite heroes, reveal the properties of inanimate matter. We can feel its weight and hardness, its elasticity and lightness, its glossy smoothness and the porous roughness of objects, the infinite variety of properties inherent in it. They influence their surroundings, from which emerges their special significance and sense of completeness.

A letter written in 1956 reminds us of yet another still life, ‘Sea shells‘. This work has been reproduced in the journal ‘Young Artist’ (1984, No. 12). E. Rybakova wrote about it: “In the last years of her life, when it was difficult for Serebriakova to leave her studio, she concentrated on painting still lifes. One of the numerous examples is ‘Sea shells’. Having arranged the fruit of the sea in the foreground, the artist seemingly invites us to marvel with her at the inner glow of the pearly pink and golden shells, at the wealth of nuance and colour, at the play of light. The mastery with which the painting is executed inadvertently reminds the viewer of the Dutch masters of the 17th century.”

[Loosely translated from Nadezhda Tregub, “The Still Life, as seen by Serebriakova“]

Still life with attributes of art. (1922)

Still life with attributes off art. (1922)

Katya and still life. (1923)

Still life with herring and lemon. (1923)

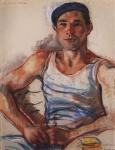

Baker on rue Lepik. (1927)

Apples on branches. (1930)

Still life basket with sardines. (1930)

Still life basket of pears. (1932)

Still life with asparagus and strawberries. (1932)

Still life basket with apples (1934)

Still life basket with flowers. (1934)

Still life with fruit. (1935)

Still life with fish on greens. (1935)

Still life with vegetables. (1936)

Still life with cabbage and vegetables. (1936)

Still life basket with grapes. (1936)

Still life with vegetables. (1936)

Grapes. (1936)

Still life basket with melons and squash. (1938)

Still life with apples and round bread. (1948)

Still life with pitcher. (1952)