An anthology of works in honour of Anna Akhmatova, the great Russian poet, was published in 1925. There were contributions of poetry from Alexander Block, Nikolai Gumilev, Fyodor Sologub, Mikhail Kuzmin, Osip Mandelshtam, Marina Tsvetayeva among others, interspersed with portraits of the poet by Nathan Altman and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, drawings by Yuri Annenkov, a silhouette by Evgeny Belukha, a statuette by Natalia Danko. At the time, Akhmatova was scarcely 35 years old, and not even half her life had been lived. Still, it was a suitable summary of her accomplishments and of the era, that of the Russian art nouveau, one of the main figures of which was Anna Akhmatova.

For long years, Akhmatova was forgotten, ignored and cursed as the spectre of socialist realism took over Russia. Yet artists continued to paint her picture, and poets glorified her poetry.

Today, the Museum of Anna Akhmatova recognises over two hundred portraits painted by her contemporaries – portraits in the graphic arts, fine art, sculpture, and even mosaic. Poetry addressed to Akhmatova are published in anthologies.

During her lifetime, her portraits were painted by such great artists as Amedeo Modigliani as well as dilettantes such as Joseph Brodsky and Georgi Shengeli. In any event, all of them are important, even if only as documentation. Sometimes they depict her likeness, and sometimes her state of mind. Sometimes they are a reflection of the internal world of the model, and sometimes they are a reflection of the relationship between the artist and the model. And there are times when we can’t even say there was a relationship at all between the painter and sitter: we do not know if Akhmatova was acquainted with Evgeniy Belukh, Maria Sinyakova, Tatyana Skvorikova. At such times, the image is less interesting as a portrait of the poet than as an illustration of the epoch.

If we trace the chronology of Akhmatova’s imagery, we can see not only how she changes with age and attitude, but also the changes in the interplay between artist and model. It is worth remembering the impact of her personality and taste on the manner of execution of her portraits. In her iconography there is little of the artistic experimentation of the 1910s-1920s, although as the wife of the avant-garde art critic Nikolai Punin in the 1920s and 30s, she moved in avant-garde circles and they were hardly indifferent to her. (Indeed, it may safely be said that nearly every one of those bohemians was in love with Akhmatova.) All of them undoubtedly saw her as ‘classically austere’, and this partly determined the style of her depiction.

What is the secret behind Akhmatova’s portrayals? What prompted her contemporaries to explore her appearance for nearly six decades? There is no simple unique answer to these queries.

Eric Hollerbach wrote to Akhmatova in 1922, and apologised for some indiscretion he committed: ‘I think that it is my awkwardness before you is a completely unconscious reaction to that sharp, dark, almost continuous ache provoked in me by your existence.’ Something had to be done about this ache, and Hollerbach dedicated poetry to his muse, and published the aforementioned anthology ‘The Image of Anna Akhmatova’.

In the modernist tradition of the time, it was the vogue to use a beautiful woman’s face to illustrate a cultural association. So we find the likes of Lyubov Delmas portrayed as the gypsy Carmen, or Ida Rubinstein as the wounded lioness of the Assyrian relief (by Valentin Serov, 1910; or Leon Bakst, 1921), or Olga Hlebova-Sudeikina as Columbine (Sergei Sudeikin, 1915), or Salome Andronnikova as “Lenore, Solominka, Ligeia, Seraphita” (from the poem by Mandelstam).

Akhmatova herself became a muse for sundry artists only after her development as a poet. In her early married years she was shy, but with the publication of her poetry, she was seen as quietly majestic (in Kornei Chukovsky’s words: ‘… In her eyes and posture and her dealings with people appear the chief feature of her personality – majesty. Not arrogance, not pride, not haughtiness, but majesty, regal, …, unshakeable confidence and self-respect for her own high literary mission.’). Even in later years, anyone who knew her felt her ‘tranquil importance’ and treated her with special respect, although she remained simple and friendly with them all.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

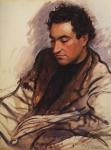

Sketch of Anna Akhmatova, by Amedeo Modigliani. (1911).

This ‘tranquil importance’ was first felt and reflected in her portrait by Amedeo Modigliani in 1911, the only one of sixteen [that he gave her] which survived with Akhmatova. He portrayed ‘the thinnest woman of St Petersburg’, as she called herself – she is grand, like the Egyptian sphinx. Akhmatova commented on the enigmatic work: ‘Modigliani was very sorry that he couldn’t understand my poetry, and suspected they concealed something miraculous.’ This portrait begins the Akhmatova iconography, not least because it survived and no earlier work is known today.

Sketches of Anna Akhmatova, by Amedeo Modigliani. (1911).

Anna Akhmatova, by Amedeo Modigliani. (1911?)

Anna Akhmatova as Acrobat, by Amedeo Modigliani. (1911?).

Head with chignon, by Amedeo Modigliani.

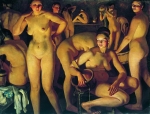

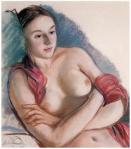

On the other hand, Modigliani’s works that were attributed in 1993 as portrayals of Akhmatova have no dates. Most likely they were created [in 1911], but it’s also possible that they were committed later, from memory: Akhmatova herself had no recollection of them. These are ‘nudes’: in the structure of her figure, there is a chaste wholesomeness, while in the pose is a dramatic expressiveness. Small wonder that her husband Gumilev had proposed that she take up dance.

The appeal of Akhmatova as a model was not merely in her unusual appearance and not just in her fame after the publication of her books ‘Evening’ (1912) and ‘Rosary’ (1914), but also in how she met the gaze of the artist, and in how she helped him see in her something greater than a poetic rule maker or lady of fashion.

Anna Akhmatova, by Sergei Sudeikin.

Sergei Sudeikin sketched a profile of Akhmatova in the early 1910s, and – using words from her poem – said it was ‘like a black-figured vase’. Alexander Tinyakov wrote to Boris Sadovsky in 1912: ‘Akhmatova is a beauty, an ancient Greek.’ Certainly, the appeal to classical references were common at the time … She was referred to as Sappho by the mosaic artist Boris Anrep; the poet Yuri Verkhovsky wrote of her (‘I heard the girl – singer of love – on Lesbos isle’).

Anna Akhmatova, by Natalia Danko (painted by Elena Danko). (1924).

In 1925, Pavel Luknitsky wrote in his diary: ‘She showed me a lead medal with her profile, and said she loved it. I noted that the profile was heavy. “That is what I like … It implies an ‘antiquity.'”‘ There is no trace of that medal. It is possible it is one of the works of Natalia Danko, along with her cameos of Akhmatova which were made of porcelain, paste and plaster.

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, by Nina Kogan. (1930).

[There is a sequence of silhouettes in the Akhmatova iconography: two by Elizabeth Kruglikova from the 1910s; Vasily Kaluzhnin portrayed Akhmatova as a character from Dante in the 1920s (reminiscent of Dante’s own profile pictures by Giotto, Raphael and Botticelli); three works by Nina Kogan in the first half of the 1930s, and finally, two by Sergei Rudakov in 1936.

Compassion, by Boris Anrep. (1952).

The sculptor and mosaicist Boris Anrep met Akhmatova between 1914 and 1917, and was so struck by her that years later, in 1952, he portrayed her (from memory!) in his mosaics (she appears in the panel ‘Compassion’ in honour of the fallen in the siege of Leningrad where she is being saved by an angel from the horrors of war; likewise, in his mosaic of St Anne, the face of the saint is said to be that of Akhmatova).

The appearance of an elderly Akhmatova was also of interest to artists. The actor Alexei Batalov said that she resembled a subject of Renaissance paintings. ‘Going by the self-portrait of da Vinci as an old man, she could have been his sister, but at the same time the doge of Venice in disguise or a Genoese merchant.’ In 1952, at Akhmatova’s request, he created her portrait with as much skill as he could muster.

Portrait by Savely Sorin. (1914).

The iconography of Anna Akhmatova can be divided into three periods. The earliest portrayals are focussed mainly on a reflection of the external – her beauty, brilliance, originality, extravagance and style. Some of them are virtually salon paintings; indeed, she called her portrait by Savely Sorin in 1914 a ‘candy box’.

Akhmatova’s (poetic) triumph is reflected in Nathan Altman’s work. The severity and novelty of (Akhmatova’s) acmeism, the sharpness and originality of her poetic sound, and the sharpness of Akhmatova’s silhouette led Altman to the use of Cubist techniques, new to Russian art.

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, by Nathan Altman. (1914).

Akhmatova’s poetry and image gradually became the standard for women’s poetry and indeed their appearance. Many adopted her image from her ‘self-portraits’ and Altman’s portrait. However, not everybody was willing to see in Akhmatova the ‘lacquered doll of Altman’ (the words of Vladimir Milashevsky).

Portrait of Akhmatova, by Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaya. (1914).

If Altman sharpened her features, Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaya softened them, conveying a feminity to the model, and (as she wrote), a ‘spiritual communion’ with her.

Portraiture session, by Nathan Altman. (1914).

Halt of Comedians, by Sergei Polyakov. (1916).

The early Akhmatova iconography is panegyric, yet includes a number of cartoons. Sergei Polyakov’s caricature ‘Halt of Comedians’ (1916) allows us to see Akhmatova amongst the guests of that literary and artistic cabaret – in the same pose as depicted by Altman. There is also a self-portrait by Altman in which he depicts a portraiture session with Akhmatova. People of the Silver Age loved to laugh at themselves: this was the antithesis of the seriousness of their quotidian lives.

Portrait of the poet Anna Akhmatova, Yuri Annenkov. (1921).

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, by Yuri Annenkov. (1921).

In 1921, Yuri Annenkov made two sketch portraits of Akhmatova in one day. The sketch executed in pen (ink and black water-colour) can be considered the beginning of the second period in the Akhmatova iconography. The transitional boundary between the periods is evident, especially since the other sketch, executed in gouache and finished by the painter in exile, can be entirely placed within the first period. [Annenkov referred to Anna as a sad beauty, a seemingly humble hermit, clad in the fashionable dress of brightness, and surely this refers to her decadent portrayal in his gouache, looking back to pre-Revolutionary times. In 1921, a year of starvation and executions, Akhmatova should more accurately have been portrayed quite differently. Akhmatova recalled having to wear the same dress for a whole year, losing weight dreadfully, becoming very poor.]

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, by Zinaida Serebriakova. (1922).

Anna Akhmatova, by Lev Bruni. (1922).

Anna Akhmatova, by Kuzma Petrov-Borodin. (1922).

The following year appeared the lyrical, beautiful portrait of Akhmatova by Zinaida Serebriakova, and the diametrically opposite, unattractive, portrait by Lev Bruni. There were also studies and a portrait by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. These works confirm that before us is no longer the poet of ‘Rosaries’: Akhmatova’s ‘Anno Domini’ was released that year, a funerary lament for Gumilev (her husband, who had been executed that year) and Blok. And while in the second period of Akhmatova’s iconography, there are graceful works (such as by the Danko sisters, or Georgi Vereisky), the focus of most artists was not so much her outward charm as the creative beginnings and fate of the poet.

Anna Akhmatova, by Georgi Vereisky. (1929).

Between 1926 and 1928 appeared the brilliant series of portraits by Nikolai Tyrsa, snatching the poet from the flow of time in different angles and conditions. Her beauty doesn’t overshadow the main impression of the portraits: she has turned inwards, into the depths of her being. Tyrsa’s work demonstrate that the inner condition and the external manifestation are one and the same, a unified embodiment.

Anna Akhmatova, by N. A. Tyrsa. (1927).

Anna Akhmatova, by N. A. Tyrsa. (1927).

Anna Akhmatova, by N. A. Tyrsa. (1927).

Anna Akhmatova, by N. A. Tyrsa. (1928).

Anna Akhmatova, by N. A. Tyrsa. (1928).

Rounding out the second period of the Akhmatova iconography are the portraits from the 1940s. First, we have the series of works by Alexander Tischler in 1943, of which the literary critic and translator Vladimir Muravyov (a friend of Akhmatova since the 1960s) said, “If all of Tischler’s portraits are put together, they really do resemble her in my opinion.. I see Tischler as a reflector of reality in the magic mirror of art.”

Akhmatova, by A. G. Tischler. (1943).

And then we have the reverent pieces of Antonina Lyubimova (which I am unable to find images of). And we have the drawings by Martiros Saryan from 1946, although it can be said his painting of that same year perhaps belong more properly to the third phase of Akhmatova’s iconography because there’s little semblance between it and the etudes he had executed.

Akhmatova, by Martiros Saryan. (1946).

Portrait of Akhmatova, by Martiros Saryan. (1946).

To the end of the second period, we can also attribute the work by Józef Czapski, litterateur, artist and fighter for Polish independence. He met Akhmatova in 1965 in Paris, and struck by the change in her appearance, sketched her in retrospective, as he had seen her in Tashkent in 1942. The nervy and sharp line, the original style is all reminiscent of perhaps the first period of the iconography.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Akhmatova continued to be portrayed by many, but the works of these decades are less interesting than those of the preceding ones. Previously, a new portrait of Akhmatova was often an event both for the artists and the public; now, there was hardly any response either from the viewers or the poet (who usually was unaware of its existence); often the artists themselves felt dissatisfied with their creations.

In the 1960s there was a spate of sculptural portraits of Akhmatova: works by Tamara Silman, Zoya Maslennikova, Lev Smorgon, Vasily Astapov, Ilya Slonim. Akhmatova’s visage, always ‘sculptural’, now demanded to be portrayed as sculpture.

The reason for the static and excessively memorialised late works comes not just from personal approaches of the artists and the pressure upon them from the weight of Akhmatova’s fame, but also from the poet’s ‘grand’ manner of posing, herself becoming a ‘monument’ and often wanted to see herself depicted as such. Otherwise, she felt, she would be defenceless beneath the gaze of the artist.

Anna Akhmatova, by Georgy Ginsburg-Voskov. (1965).

Anna Akhmatova, by Georgy Ginsburg-Voskov. (1965).

But it’s worth recalling that Akhmatova’s image in her last two decades in numerous memoirs is not quite so static. In the words of Georgy Ginsburg-Voskov who met Akhmatova in 1964: “I was infatuated at first glance… Irrespective of her age, she exuded the energy of a beautiful young woman. And evidently she charmed people: black kimono, barefoot in sandals, a pedicure, beautiful hands, ring with dark stone…” He was especially struck by her head, the power from it, the variety of angles, a different appearance from every angle. He drew Akhmatova in 1965, two portraits surviving to this day, one in profile, one en face. To his good fortune, he was able to capture her as he saw her on first meeting. This is what he wrote about the process of creation of the drawings:

I’m sitting with AA in a room. Between us is a table. On it is a vase with roses, dark red. I begin to draw her. Timidly, two old women (likely acquainted with her) open the door to ask AA to go for a walk. AA: ‘We are busy.’ – and slyly smiles at me. The old women retire. AA takes out a mirror and a comb. Looks in the mirror and straightens her fringe. I am dazed and I say, ‘Anna Andreevna, you are posing to me as though to … Durer!’ AA: ‘Yes, that’s whom I love.’

AA: ‘Garrik! You are looking at me so sternly!’ I draw as though in a fever. It feels as though she is the one who is drawing, not I. And so it was all the time.

Once AA gave me her ‘Poem Without a Hero’ to read. I sat and read. Anna Andreevna went out and returned and asked me what I think. ‘It reminds me of a medieval town with many towers.’ AA: ‘Solzhenitsyn said the same thing to me.’

Under the strong influence of ‘Poem’, I drew the picture ‘En face’. Rather, I began it. I finished after a few days, when Carlo Riccio, Akhmatova’s Italian translator and publisher was visiting her. I remember, he laughed and said, ‘Doesn’t look like her.’ When AA posed for the picture, on her head had been a round cape of coarse lace, and under her chin just to the left was big silver brooch. In the drawing at the lower left (on her left), barely perceptible (but more visible in the original) is an image of a large boulder with fir trees behind it. This was in memory of our conversation about Karelia when I was drawing her. AA had said that there were huge boulders, like the skulls of giants.

Anna Andreevna saw both drawings in nearly finished form. During the drawing of her profile, she remarked (touching her nose), ‘The nose – that’s mine. Anyone can recognise me.’

In later years, Akhmatova loved to be around young people. This communion signified, for her, an involvement in life. Zoya Tomashevskaya recalled Akhmatova’s bearing around the circle of young poets (Bobyshev, Brodsky, Neyman, Rhein): “I saw that she had a bouquet of floors, and teased her, ‘Look, the boys have brought flowers for you.’ ‘Yes,’ replied Anna Andreevna, ‘I play every role with them – from grande coquette to comic old woman.’ This was very characteristic of her: witty and easily ironic. She used to say that irony was the ability to rise above oneself. She was unusually ironic and was able to manifest it in her bitterest moments.”

And yet there’s not one portrait of a smiling Akhmatova. Probably Akhmatova herself did not allow such a possibility.

Akhmatova, by Moses Lyangleben. (1964).

Akhmatova, by Gerda Nemyonova. (~1965).

Completing the chronological overview of Akhmatova we note that in her later years appeared the expressive drawings of Leo Smorgon, Moses Langleben, Vladimir Lemport and Joseph Brodsky. The most vivid image of Akhmatova’s last period perhaps come from the numerous sketches of Gerta Nemyonova. Some of the best of them combine timelessness and instantaneity.

(The above text includes a loose translation (italicised) from [1])

References

1. Olga Rubinchik, «Я здесь, на сером полотне…» – Ахматова и художники, Toronto Slavic Quarterly, No 11 (Winter 2004)

The world of Russian culture has had an immeasurable loss, said the Russian ambassador to France, Alexander Orlov. The ambassador is indubitably correct – and not just because owing to Ekaterina’s efforts, her mother’s legacy was preserved. Zinaida was one of the greats of Russian art, one of the first women to write her name in bright letters in its history. Ekaterina herself was an extraordinary talent – with pleasure she painted watercolours of landscapes and still lifes, and (in modern parlance) undertook grand design projects in wealthy suburban mansions. However, she never shouted out her talent. For most of her life, she remained in the shadow of her mother and her brother Alexander. Only last year did Ekaterina Serebriakova dare to exhibit her work to the judgment of the public.

The world of Russian culture has had an immeasurable loss, said the Russian ambassador to France, Alexander Orlov. The ambassador is indubitably correct – and not just because owing to Ekaterina’s efforts, her mother’s legacy was preserved. Zinaida was one of the greats of Russian art, one of the first women to write her name in bright letters in its history. Ekaterina herself was an extraordinary talent – with pleasure she painted watercolours of landscapes and still lifes, and (in modern parlance) undertook grand design projects in wealthy suburban mansions. However, she never shouted out her talent. For most of her life, she remained in the shadow of her mother and her brother Alexander. Only last year did Ekaterina Serebriakova dare to exhibit her work to the judgment of the public.

.jpg!Blog.jpg)