I am not entirely sure how Zinaida Serebriakova got involved in her ballet series. Was she given a commission? Or was it owing to the interest of her neighbours, the ballet critics D. D. Bushen and S. R. Ernst? Or did it all start when her daughter Tata (Tatyana) began to train for the ballet herself in the winter of 1921? In January 1922, her mother wrote to her brother: ‘This winter, we plunged into the world of ballet. Zina draws the dancers thrice a week, one of the younger ballerinas posing for her; Tatochka twice a week at the ballet school; then Zina goes with her sketch-book behind the scenes to capture the various forms of ballet. All this because our tenants are obsessed with the ballet, and twice a week – Wednesdays and Sundays – they always go to the ballet.’

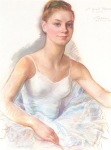

That same year, several of Zinaida’s paintings appeared: ‘Portrait of a ballerina, L. A. Ivanova performing a pas de trois from N. Cherepnin’s “Le Pavillion d’Armide”‘, ‘Portrait of M. H. Frangopulo’, ‘Portrait of E. A. Svekis’, ‘Portrait of a ballerina, A. L. Danilova, in costume for N. Cherepnin’s “Le Pavillon d’Armide”‘. Younger dancers were portrayed in costumes of the prima ballerinas of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ (Svekis), ‘Carnival’ (Frangopulo), and as Ivanova and Danilova from “Le Pavillon d’Armide”. In keeping with their character, the ballerinas posed standing or sitting as though preparing for their upcoming role in the ballet. For the most part very beautiful and svelte, they proudly held their heads high. These were dancers already experienced in the glory of success, plunged in the excitement of the theatrical scenes, graceful and feminine, fully aware of their maiden charms. They are calm and a little shy. Restrained and refined in her costume (designed by Benois) of white, green and purple for the ballet “Le Pavillon d’Armide” is Alexandra Davidova (then soloist of the Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet). Gazing upon the viewer with her huge brown eyes, with curiosity and silent questioning is Lydia Ivanova in a lush red dress and adorned with large pearls (also designed from a sketch by Benois). Smouldering with passion is Marietta Frangopulo in a wonderful Oriental robe. With a three-quarter turn of his head and parted lips is the future Balanchine in a suit of Bacchus from Glazunov’s ballet “The Seasons.” This was the only portrait of a man in that series on the ballet.

These were mainly works in pastel. As Tatyana later wrote, they were executed in Zinaida’s unique manner, with overlays and light and shade and feathering. ‘In their density of colour and pattern, their severity and brevity, they are not inferior her other works that were accomplished in oils.’

All these portraits were displayed at the 1922 ‘World of Arts’ exhibition in St. Petersburg. They resonated widely. The critic Somov wrote in his diary, ‘I tried to persuade Zina to make a big ballet painting based on the studies I had seen.’ In the years following, Zinaida created several more portraits and figuratives pieces in the series. The ballerina E. N. Geidenreich appeared several times; her most expressive portrait is ‘Portrait of E. N. Geidenreich in a white wig (1924)’ where she appears mature, full of wisdom and refinement. The series of figurative works with young ballerinas in their costumes from various performances were somewhat monotone in their light backgrounds, despite rather sophisticated harmonies of colour. Zinaida apparently had deep empathy for the inner richness of Valentina Ivanova, whom she painted several times, aiming to provide to her series the decisiveness of portraiture. Meanwhile, the portraits of Svekis were interpretations of scenes in the dressing room, but they were executed in Zinaida’s studio off her sketches.

Her daughter Tatyana recalled: “At home we were often visited by dancers. My mother bought tutus, bodices, vests, shoes – the full attire of a ballerina, and she would wear it, standing in front of a mirror and posing as she imagined her compositions. She loved and appreciated Degas, but in her works devoted to the ballet, she went her own way, and saw the world with her own eyes.”

The last pastels in their motifs and structure are reminiscent of the genre of ballet works by Edgar Degas or Konstantin Somov. It is characteristic of Zinaida that she did not paint scenes of balletic action or ballerinas learning their steps, or mise-en-scenes with standing or seated figures in their tutus (as did Degas). Her paintings concentrated instead on the relatively quiet periods in the changing room, prior to the energetic explosion on stage, when the performers are talking softly to each other, repeating a step, or getting dressed. She captured the moment that the young ballerinas transformed themselves, with their makeup and costumes, into the iconic images of swans, snowflakes, sylphs. Occasionally she shows a group of dancers in the wings, awaiting their turn to enter the stage.

The representations of the ‘Dancers in Blue’ show up the differences in the styles of the two masters, Degas and Serebriakova, both such great lovers of the ballet. While the French Impressionist was primarily concerned with the beauty of human forms and their interactions in dance, the Russian painter was interested in the richness of the atmosphere surrounding a theatrical performance. Compare Degas’s 1899 work ‘Blue Dancers’ with Serebriakova’s ‘Ballerina in Blue’ of 1922. Serebriakova is able to extract masterfully all the possibilities of oil paints and pastels, which allowed her to enact the subtleties of colour and harmony. Her ‘Snowflakes from Tchaikovsky’s ‘Nutcracker” (1923) wonderfully illustrates this possibility in her pastels, while her oils focus on the beauty of the young dancers’ bodies in ‘Snowflakes in the changing room. Tchaikovsky’s ‘Nutcracker”. As a rule, Zinaida sketched over two days her subjects in the changing room of the Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet, and then retired to her studio to work on her composition, off and on verifying to herself the poses and postures of her favourite heroines.

Scenes from dance and ballet have been set and accomplished by many artists down the ages, each doing them in their own style. Zinaida Serebriakova concentrated on the lives of famous and not-so-famous ballerinas in their changing rooms.

‘I have never thought about the ‘style’ of my oeuvre, but I think that my fascination with the great masters has, of course, had an immense impact on me,’ wrote Zinaida Serebriakova.

- Portrait of M. H. Frangolupo (1922)

- Portrait of A. D. Danilova in costume. Le Pavillon d’Armide (1922).

- Portrait of I. A. Ivanova (1922)

- Portrait of E. A. Svekis in costume (1923)

- Portrait of E. N. Geidenreich in red (1923)

- Portrait of E. N. Geidenreich in Blue (1923)

- Portrait of E. N. Geidenreich in white wig (1924)

- Portrait of V. K. Ivanova in Spanish costume (1924)

- Portrait of V. Ivanova in Spanish costume (1924)

- In the changing room. Swan Lake. (1924)

- Blue Dancers, by Edgar Degas (1899)

- Ballerinas in blue (1922)

- In the changing room (Bolshoi) (‘Pharaoh’s Daughter) (1922)

- In the changing room. Snowflakes (from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker) (1923)

- In the changing room (1923)

- Ballet les sylphides (Chopiniana) (1924)

- In the changing room (1924)

- In the changing room (1922-1924)

- Portrait of Murielle Belmondo. (1962)

.